The expedition to the jungles of Irian Jaya began at Everest Base Camp. A few years ago I joined a group of Spanish friends in an ill-fated attempt to climb Everest.

Base Camp in the pre-monsoon climbing season had turned into a battleground for the revival of the Cold War on the roof of the world. An American commercial expedition whose punters had paid upward of $50,000 each to have a go at Everest was busily firing off angry faxes to the mountaineering authorities in Kathmandu. They were in a rage over a Russian team that they claimed was using the American team’s fixed ropes. The Nepalese issue a limited number of permits to expeditions for specific routes. The south-east ridge being the least challenging, it is heavily booked by commercial expeditions with enough cash to line the pockets of the relevant bureaucrats.

In spite of the daily drudgery at Base Camp, which did not resemble mountaineering so much as trench warfare, I considered myself a rather fortunate fellow. I was having immense fun with my Spanish companions and I shared a tent with César Pérez de Tudela, our expedition leader and one of Spain’s most distinguished mountaineers.

The most technical and dangerous climbing on the classic south-east ridge route is the start, or the finish for those on their way down. This is the Khumbu Icefall, a mile long, 2,000 foot high jumble of ice blocks, some as large as churches, that spills down from the lip of the Western Cwm, itself a vast bed of glacial ice where expeditions set up their Advance Base Camp, ABC in mountaineering jargon. The Icefall is constantly shifting, slowly and imperceptibly, and without a moment’s warning a huge block of ice will snap loose under pressure and come thundering down, taking with it fixed ropes, crevasse ladders and anyone unfortunate enough to be in its path.

Things had started to go wrong the day we arrived at Base Camp, struggling to set up our tents, with the wind howling down the glacier, driving snow before it. Manolo, one of our strongest climbers, was down with a severe chest infection. This threw into disarray César’s plans to take Manolo as his climbing partner in the first summit bid.

After a few days our food supplies started to run low. Only a trickle was coming up intermittently on yaks from Namche Bazaar. We were hit by the worst piece of luck the day our Inmarsat satellite telephone crashed. This meant César had no way of sending his newspaper stories to Madrid. In the following days, as we laboriously shifted supplies up the Icefall to ABC, an unspoken tension descended on us like an invisible hand. It was getting late in the climbing season and we were making agonisingly slow headway. César knew we were dropping behind the bigger and better-equipped expeditions that had already stocked their high camps. They were now starting to push on to the South Col, the launching pad to the summit of Everest.

As the clock ticked closer to the oncoming monsoon, he began making mistakes that were to cost him dearly. Whenever one of the Sherpas appeared at our tent with a mug of tea, César would send him away with a scornful wave. ‘Can’t you use your English to tell him to leave me alone?’ he growled. In vain I warned him of the risks of not taking enough fluids.

César was still awake one night when I crawled back in through the flap after answering nature’s call. With my cap snugly stretched over my ears and the sleeping bag tugged up round my neck for good measure, I listened to the faint, steady scratching of his pen.

‘César, you (I) must be totally knackered,’ I pleaded. ‘You (I) really need to get some sleep.’

‘I’m just making a few notes. I need to have the story blocked out so I can transmit it on the Inmarsat when I get back tomorrow.’

‘When you get back back from where?’

‘I’m taking another load up the Icefall in the morning. I’ll be off before dawn, so apologies if I wake you.’ With that he switched off his head torch, tucking his pen and notebook into a stuff bag stitched to the tent wall.

‘Hang on a minute, are you sure that’s a wise thing to do?’ I said.

César retorted with a snort, ‘We’ve got to make some headway or we’re going to miss our window on the weather. Either we move now or we pack up and go home. Go on, get some sleep. It’ll be all right.’

It was anything but all right, as we found out the next morning at breakfast.

César’s walkie-talkie crackled to life at eight-forty, twenty minutes ahead of schedule. César’s voice was laboured, full of foreboding of calamity. ‘I think I’m about halfway up the Icefall… I can’t stand up… my chest… the pain is spreading to my arms…’ His voice faded in and out with the hiss and static, sharpening the sense of dread. Manolo sprang into action. He made a stumbling dash across the twenty yards of frozen moraine to the Spanish Army expedition tents. A few moments later he was back with Kiko Arregui, the expedition doctor who cupped his hand to the handset that was erupting with urgent bursts of static. ‘César, Kiko here. Listen, I want you to relax, sit down with your back propped against the ice, keep your knees raised and undo any shirt buttons around your neck. Got that? Now tell me about the pain. Where is it and how severe?’

‘Kiko, it’s very tight in my chest, very difficult to breathe… everything’s swimming round… Send one of the fast Sherpas, Chenrezi… my Trinitrate tablets, they’re in the tent… the first-aid kit…’.

Kiko turned to the four of us hovering over his shoulder. ‘A fifty-something-year-old heart attack victim trapped in the Icefall twenty thousand feet up on Everest. What a scenario.’

Chenrezi translated this to the other Sherpas who were crouched round the transmitter. They leapt as one into their climbing boots and crampons. I radioed Kathmandu to have a rescue helicopter flown in to Base Camp the next morning to evacuate César, as these magnificent snow leopards bounded up the Icefall to search for their leader. Kiko began clearing a space in the mess tent, setting up a drip next to a camp bed.

Five hours later the silence was shattered by a whoop echoing in the distant Icefall. We scrambled to the mess tent door. The afternoon snow flurries had started to blow across Base Camp. A knot of climbers, some with binoculars screwed to their eyes, were pointing excitedly at the Icefall. After five hours of man-hauling across gaping crevasses and teetering boulders of ice the rescue party was slowly inching its way down the final delicate pitches.

César treated his heart attack as a source of irritation, a temporary setback in his climbing career. Later that year he ‘phoned me with a proposal for an expedition to an unclimbed peak, Trikora in Papua New Guinea. César had sent me rummaging through the files of the Alpine Club and the Royal Geographical Society to root out information on this fabulous 15,000-foot mountain. It struck me as odd that the combined resources of these hallowed Meccas of alpine history had failed to produce a single reference to any mountain of that name in Papua New Guinea. The reason came clear one morning after several fruitless hours in the RGS map room, when the friendly bearded keeper took an interest in my plight. ‘Trikora? The name rings a bell. I believe that’s in Irian Jaya, the Indonesian half of New Guinea. Let’s have a look.’ Indeed it was.

I rang César to give him the news.

‘Good, good, Irian Jaya it is then. I’ll leave the travel arrangements to you.’

The excitement of flying into one of the world’s last largely unexplored territories came as our Twin Otter droned through the mist-shrouded mountains of Irian Jaya. The first sensation on emerging into the cool mountain air of the highland town of Wamena is one of welcome relief after an unpleasant stopover in the malaria-infested coastal city of Jayapura. The next is one of total bemusement at the Dani tribesmen, naked except for their penis sheathes, who wander about the tarmac with detached curiosity.

The trek to Trikora required 15 porters with food for about eight days, plus two Dani warriors armed with bows and arrows to safeguard the sacks of sweet potatoes that make up their staple diet.

The walk into Trikora, the highest of peak of the Jayawijaya range that bisects Irian Jaya on a west-east axis, took us through the Baliem Valley, an eerie swampland reminiscent of Conan Doyle’s Lost World. The valley was discovered less than 60 years ago by the American adventurer Richard Archibold during a 14-month reconnaissance in his Catalina flying boat.

Our guide Justinus laid on a jeep and a lorry for the drive to the roadhead 20 miles west of Wamena, from where we trekked to Lake Habbema, the site of Archibold’s first landing in the valley. From there it was a three-day hike to a cave where we were to spend out last night before the climb. When we reached the cave we discovered we were not alone. A hunting party of half a dozen or so naked warriors squatted round a fire, unresponsive to our presence as we dumped our rain-soaked raingear and arranged our sleeping bags by the fire. Justinus told us they were Yalis, a tribe of cannibals in former days whose diet, he assured us, did not include mountaineers. The Indonesian government tourist brochure on Irian Jaya promised a land of “simple shocks”, so in a mood of sleepy resignation we crawled into our sleeping bags and hoped for the best.

Our assault on the mountain began at 3am. About an hour after dawn we wearily reached a broad moraine at the foot of Trikora. It was by now obvious that we should have established our base camp here instead of at the cave. The approach march in the dark was by far the most unnerving part of the climb. We had spent three hours struggling up a 600ft steep grassy slope, at times up to our knees in water, with nothing but mats of reeds for hand holds.

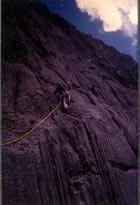

Once we started up the rock face the climbing became a delight. The holds were superb, albeit not very stable, and we were rewarded with the exhilaration of putting up a route on an unclimbed peak. The climbing rarely exceeded British grade VD (Very Difficult), but the sobering thought was always with us that had one of us taken a fall, it would have required a desperate hike of several days to reach help.

Three hours later we were on the summit pyramid, congratulating ourselves on having completed the first Trikora direttissima yet a final adventure lay head.

We returned to the roadhead outside Wamena at night in a raging downpour where Justinus negotiated a lift back to town in a jeep with an Indonesian road worker. We set off down the bending mud track, the porters following behind huddled under a tarpaulin in a lorry. Justinus sat facing me, a look of terror on his face as we sped round the sharp bends, slewing close to a sheer precipice. Our driver threw the jeep into first to take a steep uphill gradient and suddenly slammed on the brakes. The lorry had stalled some 20 yards behind, its wheels spinning in the mud. That’s when the fun began. The driver hooked a towing cable to the lorry’s front axle. After a few violent jerks we were moving slowly uphill. When we reached the top we braced ourselves for a quick stop to release the tow rope but the driver kept on speeding down toward Wamena some five miles away. We could hear mournful screams coming from under the tarpaulin in the lorry, by now completely out of the driver’s control, whose headlamps pursued us like the glowing eyes of a panther. César, who was sitting in the front seat, turned to me and we both burst into laughter. It seemed an appropriate end to the journey.