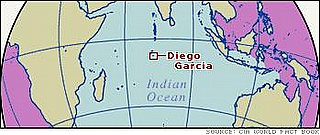

In the first of a number of Where in the World profiles, we look at Diego Garcia, a tiny island in The Indian Ocean, with coral beaches, turquoise waters and a vast lagoon in the centre. It is 1,600 kilometres from land in any direction, which seems to be the main attraction for the people who are allowed to go there. If you were ever thinking of visiting Diego Garcia, unless you are in the US or UK military, it might be wise to think again. But where is it, and why is it so controversial?

The

Portuguese

put Diego Garcia on the map in the 1500s. The island’s name is believed

to have come from either the ship’s captain or the navigator. Diego

Garcia was covered in plantations (copra, coconut, etc) in the 1800s.

Between 1814 and 1965 it was a dependency of Mauritius.

It then became part of the Chagos Archipelago, which belonged to the

newly created British

Indian Ocean Territory. The island remains a British

dependency today but is leased to the US by the British. In 1970.

The

Portuguese

put Diego Garcia on the map in the 1500s. The island’s name is believed

to have come from either the ship’s captain or the navigator. Diego

Garcia was covered in plantations (copra, coconut, etc) in the 1800s.

Between 1814 and 1965 it was a dependency of Mauritius.

It then became part of the Chagos Archipelago, which belonged to the

newly created British

Indian Ocean Territory. The island remains a British

dependency today but is leased to the US by the British. In 1970.

Once Diego Garcia had a small native population, known as the Ilois, or the Chagossians, many of whom were agricultural workers or fishermen. They were, however, forced to relocate (1967–1973) so that the island could be turned into a military base, much to strong protestations of other Indian Ocean islands, who objected to the island being used as a base for cruise missiles. Most of the Ilois now live in reduced circumstances in Mauritius’s shanty towns, more than 1,000 miles from their home. A smaller number were deported to the Seychelles. In 2000, a British court ruled that the order to evacuate Diego Garcia’s inhabitants was invalid, but the court also upheld the island’s military status, which permits only personnel authorized by the military to inhabit the island. The Ilois sued the British government for compensation and the right to repatriation, but in Oct. 2003 a British judge ruled that although the Ilois had been treated “shamefully” by the government, their claims were unfounded. Not much help, really. In 2004 the British government issued an “Order of Council” prohibiting islanders from ever returning to Diego Garcia.

A somewhat biased 2004 documentary by Australian journalist John Pilger called Stealing a Nation publicised the plight of the islanders. According to Mr Pilger, the islanders were tricked and intimidated into leaving until “the remaining population was loaded on to ships, allowed to take only one suitcase. They left behind their homes and furniture, and their lives. On one journey in rough seas, the copra company’s horses occupied the deck, while women and children were forced to sleep on a cargo of bird fertilizer. Arriving in the Seychelles, they were marched up the hill to a prison where they were held until they were transported to Mauritius. There, they were dumped on the docks.” Some of the Ilois are making return plans to turn Diego Garcia into a sugarcane and fishing enterprise as soon as the defense agreement expires (some see this as early as 2016). A few dozen other Ilois are still fighting to be housed in the UK.

Now, Diego Garcia is home to a military base jointly operated by the United States and the United Kingdom, although in practice it is said to be largely run as a US base, with only a small number of British forces and military police. No other economic activity is now allowed. The base serves as a naval refueling and support station. It is also equipped with airfields that have been used on missions to Iraq during the 1990 Gulf War, and to Afghanistan in the 2001 U.S. Attack on Afghanistan.

But still there is controversy. Human rights groups claim that the military base is used by the US government for the interrogation of prisoners (allegedly with methods illegal in the US). The British Foreign Secretary Jack Straw has said in the British parliament that the US authorities have repeatedly assured him that no detainees have passed in transit through Diego Garcia or have disembarked there. Intelligence analysts say Diego Garcia’s geographic isolation is now being exploited for other, more sinister purposes. They claim it is one of several secret detention centres being operated by the Central Intelligence Agency to interrogate high-value terrorist suspects known as “ghost detainees” or the “new disappeared,” beyond the reach of American or international law.